This article is adapted from a speech presented at CLE International’s Beer, Wine & Spirits Law Conference. It focuses on ATF’s proposed regulations; the final regulations, which became effective March 15, 1999, raise substantially the same issues.

On September 13, 1995 ATF issued proposed regulations designed to give ATF clear authority to revoke COLAs issued in error. As of October 1998, ATF still had not finalized these rules.

ATF has issued hundreds of thousands of certificates of label approval (“COLAs”) over the past several decades. COLAs are required for almost all malt beverages (imported and domestic), almost all distilled spirits and most wines. Generally, they do not expire.

Well over a million COLAs have been issued in the past several decades and most of them are still valid. Each year ATF reviews another 60,000 COLA applications. 60 Fed. Reg. 47506 (1995).

Because of the large number of approved labels, it is inevitable that every now and then ATF will regret its approval of a label. In the proposal, ATF confirms that “There is no doubt that errors will occasionally occur in the approval process.” Id.

There are a fair number of regrettable COLAs, but the number is small when compared to the total number of COLAs. Some of the more noteworthy examples of regrettable COLAs are as follows:

-

Black Death Vodka

-

Domaine Chardonnay. Despite this brand name, the wine did not qualify to be labeled as a Chardonnay.

-

Chardonnay with Natural Flavors. Some wineries recently began marketing products labeled as, e.g., Chardonnay with Natural Flavors. The varietal term appears more prominently than the rest of the designation, even though the products would not qualify to be labeled as Chardonnay. ATF sought to revoke the labels in mid-1998.

-

Bad Frog. ATF approved a label for Bad Frog beer. The label prominently features a frog raising its middle finger (as best a frog can do); it is not clear whether ATF knew this when it approved the label. The NYSLA and three other states refused to register the product. The Second Circuit decided that the label is protected commercial speech and prohibited the NYSLA from rejecting it. Bad Frog Brewery, Inc. v. New York State Liquor Authority, 134 F.3d 87 (2nd Cir. 1998).

-

Crazy Horse. ATF approved a label for Crazy Horse Malt Liquor in 1992. Two months later the Surgeon General (Antonia Novello) held a press conference in South Dakota where she criticized this brand name; she pointed out that Crazy Horse was a revered Indian leader. Congress then passed a law directing ATF to revoke the Crazy Horse COLA. The District Court decided that the statute violated the First Amendment and struck it down. Hornell Brewing Co., Inc. v. Brady, 819 F. Supp. 1227 (E.D. N.Y. 1993).

Some of these examples involve governmental efforts to force the revocation of a regrettable COLA. But even in the case of regrettable COLAs it is much more common for ATF to seek to persuade the certificate holder to surrender the COLA voluntarily.

III. BLACK DEATH CASE

The Black Death case, Cabo Distributing Co., Inc. v. Brady, 821 F. Supp. 601 (N.D. Cal. 1992), prompted the issuance of the proposed regulations and is one of the best examples of a regrettable COLA.

In 1989 Cabo acquired the rights to import Black Death Vodka and ATF promptly approved the labels. Together with the brand name, the front label has a large picture of a human skull. The skull sports a large black top hat and a broad smile.

Cabo spent over a million dollars marketing the product over the next 3 years. For example, Cabo hired a prominent rock star to promote the vodka. Cabo also packaged some of the vodka bottles within miniature coffins.

The U.S. Surgeon General was not amused; in early 1992 she appeared on the “Today” show to complain about the product. She said the product encouraged alcohol abuse on the part of young people. Within just a few days thereafter, ATF sent Cabo a letter and gave Cabo 10 days to stop selling the vodka.

The letter said the Black Death labels violate ATF regulations because they mock the very real risks associated with alcohol consumption. Though this may have been true, it was unfortunate for ATF that the laws and regulations do not cover “mocking.” ATF also claimed that the labels are misleading because they suggest that the product is poisonous.

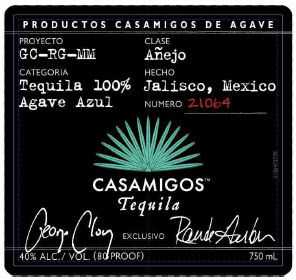

During the next several months Cabo and ATF negotiated about changing the name to Black Hat. As Cabo moved toward agreeing to these changes, sales suddenly surged, due in part to the controversy. Cabo decided to stick with the original brand name and indeed decided to expand to a Black Death Tequila which would feature a smiling skull wearing a sombrero.

ATF attempted to revoke the COLAs in June of 1992 by issuing a letter stating that all Black Death COLAs had been canceled. A few weeks later Cabo asked the U.S. District Court in San Francisco to enjoin ATF from revoking the vodka approvals. A few weeks after that, Cabo asked for summary judgment in its favor.

In granting the injunction and in granting summary judgment in Cabo’s favor, Judge Jensen concluded that issuance of a COLA creates a property interest and that the COLA should therefore be protected by the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

- Due Process

The court decided that due process had been denied for the following reasons:

- the COLAs are valuable;

- ATF had no written procedures for label cancellations;

- ATF had no criteria for deciding when to revoke a label;

- ATF decided to revoke the COLAs before it had a chance to hear Cabo’s side of the story;

- ATF created no written record of its meetings with Cabo;

- Cabo had no opportunity to challenge ATF’s position because it was based, simply, on “administrative expertise;”

- it would not be unduly burdensome for ATF to provide for the missing safeguards; and,

- it is not clear that ATF had any special expertise concerning consumer perceptions.

- Statutory Authority

The court further decided that ATF has no express authority, in the statutes or the regulations, to revoke COLAs. ATF argued that its authority to revoke is implicit in its right to approve COLAs, but the court did not necessarily agree. At a minimum, the court said ATF would need “regulatory authority.” The court went even further to state that, even if ATF had implicit authority to revoke COLAs, it would need to do so within a short and reasonable period of time after approval. - First Amendment

The court decided that the label statements were probably protected by the First Amendment.

- Arbitrary

Finally, the court held that even if ATF had followed the proper procedures, and even if ATF had clear statutory authority to revoke, all of its bases for revoking these particular labels were arbitrary and capricious.

Although ATF could not have been happy with Judge Jensen’s decision, ATF did not appeal. The attorney for Cabo has said he believes ATF did not appeal because the decision was well reasoned. It was also based on a wide variety of independent grounds (e.g., due process, First Amendment, arbitrary and capricious, lack of authority) and ATF would face the daunting challenge of prevailing on all of these grounds.

Cabo is still in business but it no longer sells Black Death.

ATF has approved 22 different Black Death labels in the past six years, since the Cabo decision. These cover a wide variety of types, including Rum, Gin, Tequila and Whiskey. The current U.S. Importer is Nations Beverage of Orinda, California.

Ironically, after all of the intervention by various levels of the federal government, the matter was most directly decided by others. At about the time of the Cabo decision, most wholesalers decided to stop carrying these products.

V. DOES ATF HAVE AUTHORITY?

Judge Jensen stopped just short of saying ATF has no authority to revoke COLAs. He said ATF has no express authority and it is clear that the FAA Act says nothing about revocations. But when Judge Jensen states that ATF may not revoke without statutory or regulatory authority, he seems to confirm that ATF may revoke COLAs if it has the proper regulatory foundation. ATF is trying to put this foundation in place.

My assessment is that ATF does have implicit authority to revoke. If you deny that ATF has any implicit powers, then where would ATF get the authority to reject? The statute and regulations are silent on rejection. But it would be ridiculous to say that ATF has no choice but to approve every label it receives. In the same way, ATF would seem to have implicit authority to revoke labels.

ATF quite apparently believes that it has statutory authority to revoke because it issued proposed regulations on this topic in 1995. The proposal is entitled “Procedures for the Issuance, Denial and Revocation of COLAs.” 60 Fed. Reg. 47506 (1995).

In the proposal, ATF says it disagrees with the Cabo court’s holdings. ATF says “it believes that a right to cancel [COLAs] is implied from the statute’s delegation to the Secretary of the authority to issue [COLAs] ‘in such manner and form as he shall by regulations prescribe.’” Id. at 47507. ATF claims this language provides it with explicit authority to issue regulations covering approvals and implied authority to issue regulations covering revocations.

ATF’s 1995 proposal provides as follows.

- Rejections

Rejections are issued by the label reviewer. If the applicant disagrees with a rejection, the applicant has only 45 days to appeal, to the Chief of the Labeling Section. Throughout the appeal process, all arguments, evidence and even requests for meetings must be submitted in writing. This differs from the current practice by being more formalized, imposing time limits, and by allowing no appeal past the Chief of the Labeling Section.

- Revocations

When the Chief, Product Compliance Branch (hereinafter “PCB”), determines that a COLA is not in compliance with the laws or regulations, he or she shall issue a notice of proposed revocation. The certificate holder then has 45 days to respond, and the Chief, PCB must respond to any such letter by withdrawing the proposed revocation or explaining the basis for the revocation. The Certificate holder has 45 days to appeal any adverse decision, to the Chief of the Alcohol and Tobacco Programs Division, and his/her decision will be ATF’s final decision.

The proposed regulations require at least a 45 day use-up (except those revoked by operation of law). The use-up may be far longer and its scope is committed entirely to the discretion of the deciding official. This differs from the current practice by being more formalized, imposing time limits on the certificate holder but not on ATF, by allowing no appeal past the Chief, Alcohol and Tobacco Programs Division, by providing a 45-day minimum use-up period, and by requiring revocations in some instances.

ATF can also revoke COLAs by operation of law. For example, if Congress changes the Government Warning Statement but ATF does not allow the revision without filing a new COLA. The appeal procedure is similar, though slightly abbreviated.

The proposal generated about 20 comments. Most of them were supportive. My own comments are followed by highlights from the comments submitted by others.

- Burden of Proof. Perhaps the burden of proof should be higher, for revocations. The proposal does not identify the burden of proof to be used, and so the normal “preponderance of the evidence” standard is most likely. Because many of the regulations call for highly subjective determinations, such as “misleading,” and because revocation of an existing COLA is drastic, ATF should provide “clear and convincing evidence.”

- Incontestable. Perhaps COLAs should become incontestable after five years. The Cabo court said ATF should not be allowed to revoke a COLA three years after approval. Another alternative would be to make the standard higher only for COLAs approved, e.g., more than 3 years prior to proposed revocation.

- Make Decisions Public. The regulations provide that ATF’s instrument for revoking COLAs will be a letter, from either the Chief, PCB, or the Chief, Alcohol and Tobacco Programs Division. When final, these decisions should be made public. They will or ought to explain the law in an area that is, almost by definition, controversial and there is no obvious reason why these decisions should not be made public. After all, the initial approval is public. Rejections are different and should continue to be confidential.

- Wine Institute. ATF should use certified mail, return receipt requested, instead of regular mail. All deadlines should be measured from receipt rather than issuance.

- Government of France. The Government of France recommended a formal role for affected third parties, so that, for example, the INAO would have a chance to oppose improper appellation references.

- NABI. The National Association of Beverage Importers recommended that the regulations should include the right to a formal hearing before an independent ALJ, in the case of both denials and revocations. Note that Cabo had asked ATF for a full evidentiary hearing, within a few days after ATF first contacted Cabo but ATF denied this request. NABI’s comment also recommended that the regulations should require ATF to decide on appeals (rejections and revocations) within 15 days.

- Government Liaison Services. GLS raised good questions about the 45-day limit for appealing COLA rejections. If a new 45-day period can be triggered merely by resubmitting the label, then the limit serves no purpose. But if not, then the regulations strongly encourage applicants to promptly appeal rejections, to keep them from being used as binding precedents, and this will greatly increase the burden on both ATF and the industry.

- Beer Institute. The Beer Institute pointed out that problems will flow from the fact that ATF is prosecutor, judge and jury.

- DISCUS. The Distilled Spirits Council argued that ATF probably has no authority to revoke COLAs. DISCUS also called for hearings before an ALJ and a heightened standard of proof (i.e., clear and convincing evidence) in those rare instances when ATF seeks to revoke. Also, DISCUS urged ATF to provide, in the case of revocations and denials, a detailed explanation of all reasons why the label is not in compliance.

IX. CURRENT STATUS

It has been more than three years since ATF published the proposal and more than two years since the comment period closed, but still no final rule has been published. Why? It could be because of uncertainty about the strength of the Bureau’s position. It could also be due to difficulties raised by the comments. In any case, in recent months ATF has frequently said that the final rules will be published in the near future.

ATF has sought to revoke very few COLAs in the past several years, since the Black Death decision and the proposal. This could be because ATF intends to use the power very sparingly, or, ATF may be waiting until the regulations have been finalized. The absence of final rules did not prevent ATF from seeking to revoke the COLAs in the case of the other than standard wine labels bearing prominent varietal claims (i.e., the “Chardonnay with Natural Flavors” labels discussed on page 1, above).

There is no clear evidence that any lack of authority (during the interim period after the Cabo decision but before issuance of final rules) has caused ATF to slow its approval of new labels. But it is to be hoped that if and when ATF gains clear authority to revoke the most inappropriate approvals, it will by contrast allow ATF to substantially speed up its approval of most labels.

The proposed revocation procedure is not altogether different from that offered to Cabo six years ago. The similarities are as follows:

- In the Cabo case, the Chief, Industry Compliance Division proposed to revoke the COLAs by letter. Under the proposal, the Chief, PCB (one level lower) will propose to revoke a COLA by letter.

- In the Cabo case, ATF gave Cabo 10 days to respond. Under the proposal, the certificate holder would have 45 days in which to respond to the proposed revocation.

- In the Cabo case, ATF met with Cabo informally, but most information was exchanged in writing. The policy would be the same under the proposal.

- Despite the animosity between ATF and Cabo, ATF nevertheless granted Cabo 90 days to use up the Black Death labels. The proposal allows at least a 45 day use-up.

- In the Cabo case, ATF procedures allowed for no formal evidentiary hearing, no transcript, and no independent judge. The proposed procedures would be the same in these respects.

Despite these similarities there are two important differences that point to the possibility of a different outcome if and when a COLA revocation is next challenged:

- ATF had no clear regulatory authority when it sought to revoke the Black Death COLAs, but ATF is very likely to have this authority in place the next time.

- In the Cabo case, Cabo argued that ATF decided to revoke the COLAs before Cabo had a chance to respond, and that ATF had a closed mind thereafter. Indeed, ATF’s initial letter to Cabo states “[ATF] has determined that the labels are in violation of ATF regulations.” The next time around, formalized revocation procedures and the lessons of Cabo should prevent ATF from deciding too early.

By early 2002, ATF had formally revoked few if any labels. Nevertheless, these contentious issues are bound to arise again.