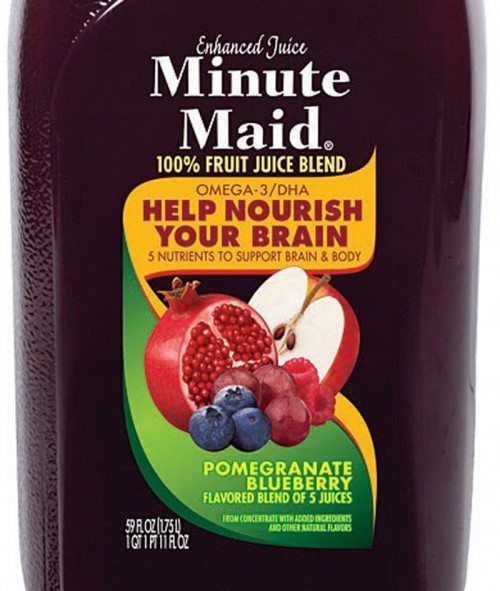

The U.S. Supreme Court, on January 10, 2014, agreed to hear Pom’s argument that Coke’s fruit beverage labels (such as the one at right) are misleading. The excellent FDA Law Blog has good coverage of the controversy here. Coke’s Minute Maid product only has a tiny amount of pomegranate juice — less than 0.5% — and so Pom (rather than the government) argues that this is misleading especially inasmuch as the labels show pictures of pomegranates.

The U.S. Supreme Court, on January 10, 2014, agreed to hear Pom’s argument that Coke’s fruit beverage labels (such as the one at right) are misleading. The excellent FDA Law Blog has good coverage of the controversy here. Coke’s Minute Maid product only has a tiny amount of pomegranate juice — less than 0.5% — and so Pom (rather than the government) argues that this is misleading especially inasmuch as the labels show pictures of pomegranates.

Pom’s superfamous lawyer argued:

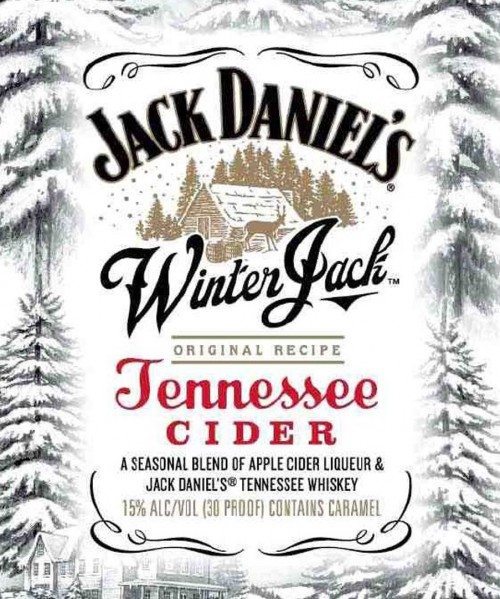

This is a classic false advertising case. Pom and Coca-Cola compete directly in the market for pomegranate juices. Pom sells juices that—as purchasers would naturally expect—overwhelmingly contain actual pomegranate juice, which is sought by healthconscious consumers. Pom’s products include a pomegranate-blueberry juice. Coca-Cola sells and aggressively markets its competing “POMEGRANATE BLUEBERRY” juice, which it colors a deep purple and sells with a label containing a large image of each fruit. … Coca-Cola’s misleading label causes consumers to believe that the juice actually contains significant amounts of those fruits when in fact it contains only trivial amounts: 0.3% pomegranate juice and 0.2% blueberry juice. … Pom introduced survey evidence showing that consumers are in fact seriously misled.

Pom also quotes a key part of the government’s brief: “Further, the ‘FDA does not approve juice labels, and its failure to initiate an enforcement action cannot be construed as such an approval.'” Other juicy tidbits courtesy of Pom include: FDA and the FDC Act “sets a ‘floor’—not a ceiling—on federal regulation of labels.” Pom explains the sweeping importance of this case, and why it is so ripe for review:

Even if it were limited to food products, the ruling below grants tens of thousands of food and juice producers sweeping immunity with respect to countless products from liability under the Lanham Act for even knowingly misleading consumers. … The government recognizes that the court’s “deference to FDA’s available but unexercised authority would arguably preclude a Lanham Act challenge to the label of any food,” including “the many foods that FDA’s regulations do not specifically address at all.” … As the GAO has confirmed, the FDA “generally does not address misleading food labeling because it lacks the resources to conduct the substantive, empirical research on consumer perceptions.'”

By contrast, Coke not surprisingly argues “the FDA has adequate resources to regulate the content of food and juice labels.” Coke further argues:

whether a multi-fruit juice name or label is deceptive is not only within the FDA’s expertise, but is a topic that the FDA has already addressed in detailed and specific regulations. … As the United States correctly observes, the regulation “reflect[s] the agency’s balance of competing considerations in a specific setting that could easily be upset by the intrusion of a general private remedy such as that provided under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act.”

Getting deep into the nitty gritty of the labels at issue and the rules, Coke proudly proclaims “Here, the letters ‘FLAVORED BLEND OF 5 JUICES’ comply with this specific regulation because, as is clear from the image …, they are more than one-half the height of the words ‘POMEGRANATE BLUEBERRY.'” Coke claims it is a big (“hyperbolic”) exaggeration to say FDA lacks sufficient resources to regulate food labels.

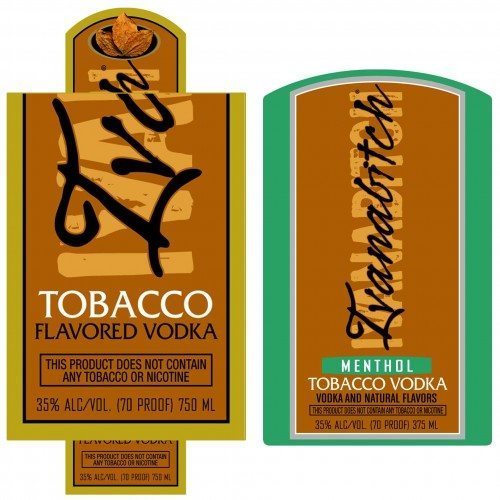

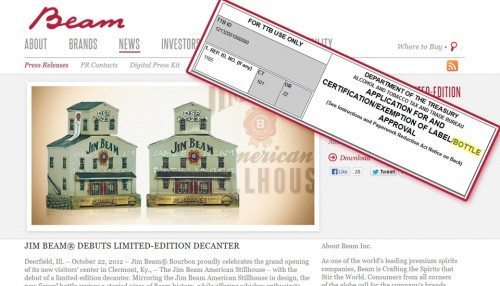

If Pom wins this battle, it will seem to be another sign that the government, step by step, as it gains powers in some areas, continues to relinquish power in other areas, to allow large segments of statutory and agency mandates to be effectively privatized (or libertarianized). For example, as here, Pom and other Coke competitors would become the reviewers of Coke’s labels every bit as much or more compared to what FDA might have done in the past. This case could have enormous implications far beyond FDA labels, and could extend all the way over to TTB labels, TTB formulas, excise taxes, TTB permits, to almost every area that alcohol beverage regulators have firmly controlled in the past. In other news, this case provides a wonderful forum for Pom to beat up on Coke, and remind everyone that Pom has more juice, up and down the U.S. court system, year after year (since at least 2008). I wonder how the cost of this lawsuit compares to or relates to an old-fashioned ad campaign in the paid media.

From our perspective, working with thousands of labels and hundreds of such questions (from the trivial to the weighty) on a yearly basis (as opposed to an appellate litigator or a judge dealing with this from time to time when it flares up big) it seems clear that such tricky questions will inevitably get “litigated.” The only question is whether they will get litigated in an agency proceeding (as has been common in the past), the media, amongst lawyers battling apart from a court or agency proceeding, or in the courts (as was fairly rare in the past). To the extent that Pom wins, we can expect a huge shift from the first to the last.