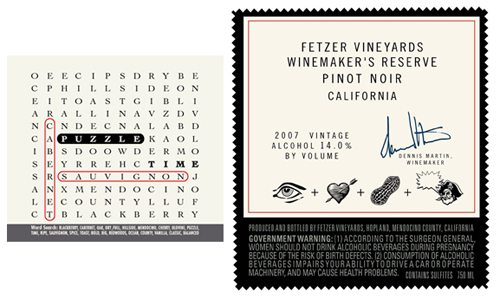

As lawyers, we would never condone playing games on wine labels. But here are two examples where TTB was okay with it.

On the left, Puzzle Time wine has a word search game.

On the right, the Fetzer label features a “rebus.” That’s right, a rebus. The approval describes a rebus as “a kind of word puzzle that uses pictures to represent words or parts of words.” Can you read the rebus on this label? I don’t want to spoil the fun here, but the answer can be found on the label approval.

Search Results for: ttb

Wine Without Sulfites

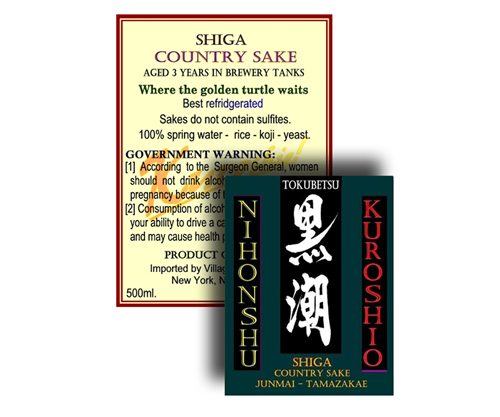

TTB classifies sake as a wine, for label purposes. Most wines have sulfites — but sake appears to be a notable exception. On the Shiga Sake label above, Village Wine reports that “Sakes do not contain sulfites.” TTB does not seem to disagree and has approved many such labels.

TTB classifies sake as a wine, for label purposes. Most wines have sulfites — but sake appears to be a notable exception. On the Shiga Sake label above, Village Wine reports that “Sakes do not contain sulfites.” TTB does not seem to disagree and has approved many such labels.

Another sake importer, Vine Connections, concurs and reports that “Premium sake is gluten-free, sulfite free, and kosher.”

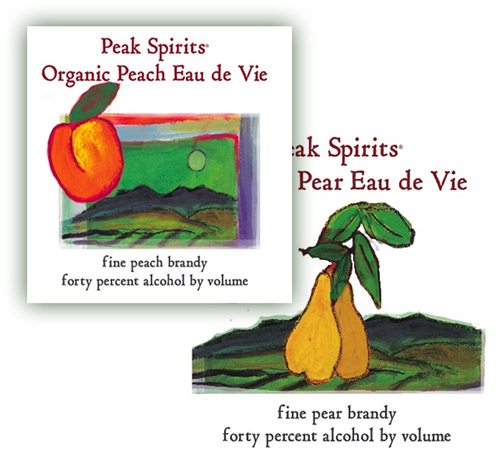

What is Eau de Vie?

Every now and then, TTB approves another eau de vie. This leads to wondering if it’s the same as brandy. At long last, Tim Patterson has explained how they differ:

Unlike grape brandy, eau de vie puts the emphasis on freshness, liveliness, and capturing the intense essence of fruit — rather than on depth, weight, and the complexity that comes from years of interaction between spirit, oxygen and wood.

By way of example, here is Peak Spirits Peach Eau de Vie. And here is Clear Creek Plum Eau de Vie. Patterson explains further:

In the market for distilled spirits, dominated by slick, multi-million-dollar ad campaigns for super-premium vodkas and single malts, eau de vie is nearly invisible. If there’s something smaller than a niche market, eau de vie has it sewn up.

Yet for those who seek it out, and are persistent enough to find it, great eau de vie can be an exquisite experience.

The name translates as “water of life,” a reminder that the invention of distillation in the 17th century came in pursuit of cures for plagues like cholera.

Put another way, eau de vie is the anti-vodka. The point of vodka distillation is to remove all those annoying flavors; the point of eau de vie is to preserve as much of the original fruit as possible.

The economics of production provide an equally stark contrast. [Vodka] can be made from almost any source … for a cost of less than fifty cents a bottle. A quality eau de vie consumes about 30 pounds of first-rate fruit, picked at the moment of peak ripeness.

I have quoted extensively from Patterson’s excellent article, and still it contains much other compelling information, such as the fact that both of the leading producers of American eau de vie happen to be lawyers. TTB does not seem to recognize eau de vie as a distinct category; the above examples are classified as brandy and have the term “brandy” on the label alongside “eau de vie.”

Where is Napa?

This looks like a straightforward label, but it raises some good issues. “Napa” is on the “brand (front)” label. Should it be? On the one hand, it looks to be bottled in the Napa Valley. On the other hand, the appellation is California more broadly, as per box 14 of the label approval. The label mentions Napa three times, attesting to its obvious importance as a signal of quality.

Each reference to Napa tends to be accompanied by a clarifying explanation. One says it’s bottled there, two say the brand’s ownership is there. None of them (explicitly or by omission) suggest the grapes were grown there. TTB has approved quite a few labels presenting the same issues, and they may show a shift in policy, compared to five or ten years ago. It is our understanding that some wineries were blocked from highlighting Napa, regardless of the location of the bottling winery, if the grapes were from elsewhere.

The same label raises one more good (but rather technical) issue. The brand name and alcohol content statement are on one piece of paper. The varietal and appellation are on another. The rules require all four items to be on the brand label. Sometimes, TTB requires all four items on the same piece of paper, sometimes in the same field of vision. Here TTB allowed them to be divided across two pieces of paper in the same field of vision.

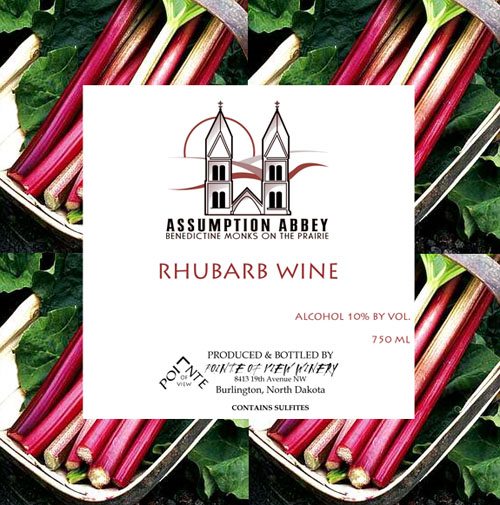

Vegetable Wine

Earlier this week we covered kiwi wine. Today, we go further from grape wine, toward vegetable wine. Rhubarb wine to be exact. Rhubarbinfo.com says it’s a vegetable and on this I will tentatively defer to them.

Assumption Abbey Rhubarb Wine is made by Pointe of View Winery in Burlington, North Dakota. The TTB database has many rhubarb wines, and they tend to be made in states not well known for grape wine, such as Kansas, Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana. None of these labels tend to show an appellation of origin or a vintage date. In a good article about non-grape wine, the San Francisco Chronicle explains:

[TTB] allows fruit wine makers to add sugar, acid and water as needed – natural flavors and colors are even allowed – but they don’t allow a fruit wine to bear a vintage or place-name the way a grape wine does.

“I think it’s a waste to not allow vintage dating,” says Koehler. “You have good and bad years for fruit, just like you do for grapes.”

Those laws aren’t likely to change, if only because of the effort required by the TTB to police them. What does vintage mean to Tedeschi Vineyards when pineapple is available year-round? What does place-name mean to Galarneau when he buys mangoes from around the world?

It is difficult to locate the rules that prevent rhubarb and other non-grape wines from showing the vintage and appellation. Perhaps an astute reader can point them out.

Milk from Dragons, Grapes and Devils

In many areas, TTB is fairly literal-minded. For example, if you are bound and determined to mention energy on your label, you are unlikely to get very far, without much regard to context, as in this example. Likewise, good luck if you want to use the term “organic” on anything not in line with the organic rules.

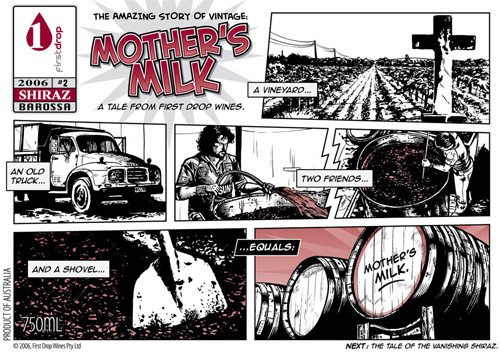

In other areas, though, TTB will view a term much less literally. Mother’s Milk Shiraz is one such example. As best I can tell, it contains no milk. There is a recognition that the term is not to be taken seriously, even though it is quite possible to make a wide variety of alcohol beverages with and from real milk. This vodka distilled from milk is but one example.

If you gave up Mother’s Milk before third grade, you may prefer Dragon’s Milk. Another alternative is Devil’s Milk. Even without ingredient labeling I am reasonably sure that the Devil contributed no milk whatsoever to DuClaw’s ale.