Palcohol is back.

After approval from out of nowhere about a year ago, and cancellation of the same approvals a few days later, it is back. I have it on good authority that TTB has ironed out the kinks and approved the labels this week. Sen. Schumer will not be pleased (aka, he may be very pleased to have this whipping boy back within striking distance). Many states have already banned it. But this gives new life to this new category. Hats off to Mark Phillips for weathering the storm and persevering.

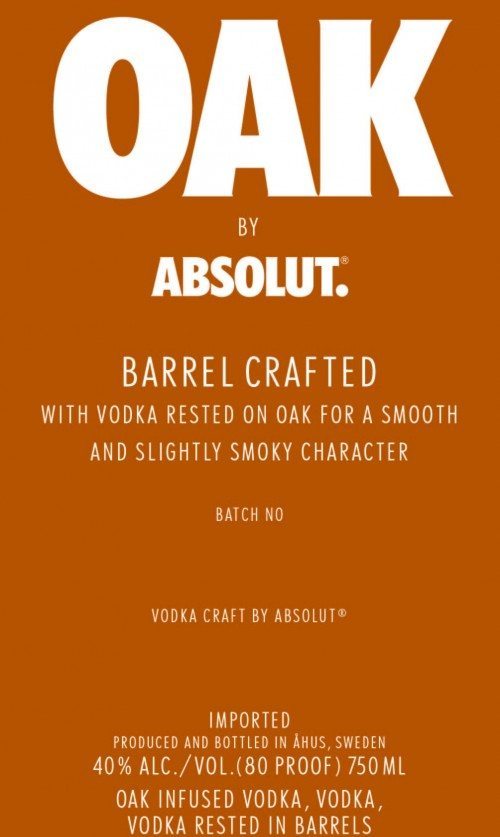

Below is the approved label as of 2014 alongside the label as approved on March 10, 2015. There are small, technical changes, mostly relating to how to measure the taxable commodity. Boxes 20 and 23 reconfirm that it took Mark almost a year to get this approval. The back label makes it look like an awful lot of work and controversy for a small amount of alcohol (when prepared, it only has half the liquid of a beer, and 1/4 the abv compared to vodka?!?).

In an email on the day of re-approval, Mark, the force behind Palcohol, explained:

Yes, Palcohol is back. It’s been quite a journey, over four years to get Palcohol approved by the TTB. I do want people to know that the TTB has been great to work with. Very fair and professional. And I’m not just saying that to kiss up to them as they have now approved Palcohol and it’s done.

The next challenge is trying to stop the states from banning it based on misinformation and ignorant speculation. It is a mistake for a state to ban Palcohol because…