Well, we may have only one retailer in the near future — AmazonWholeFoods. But we sure have a lot of beer to choose from.

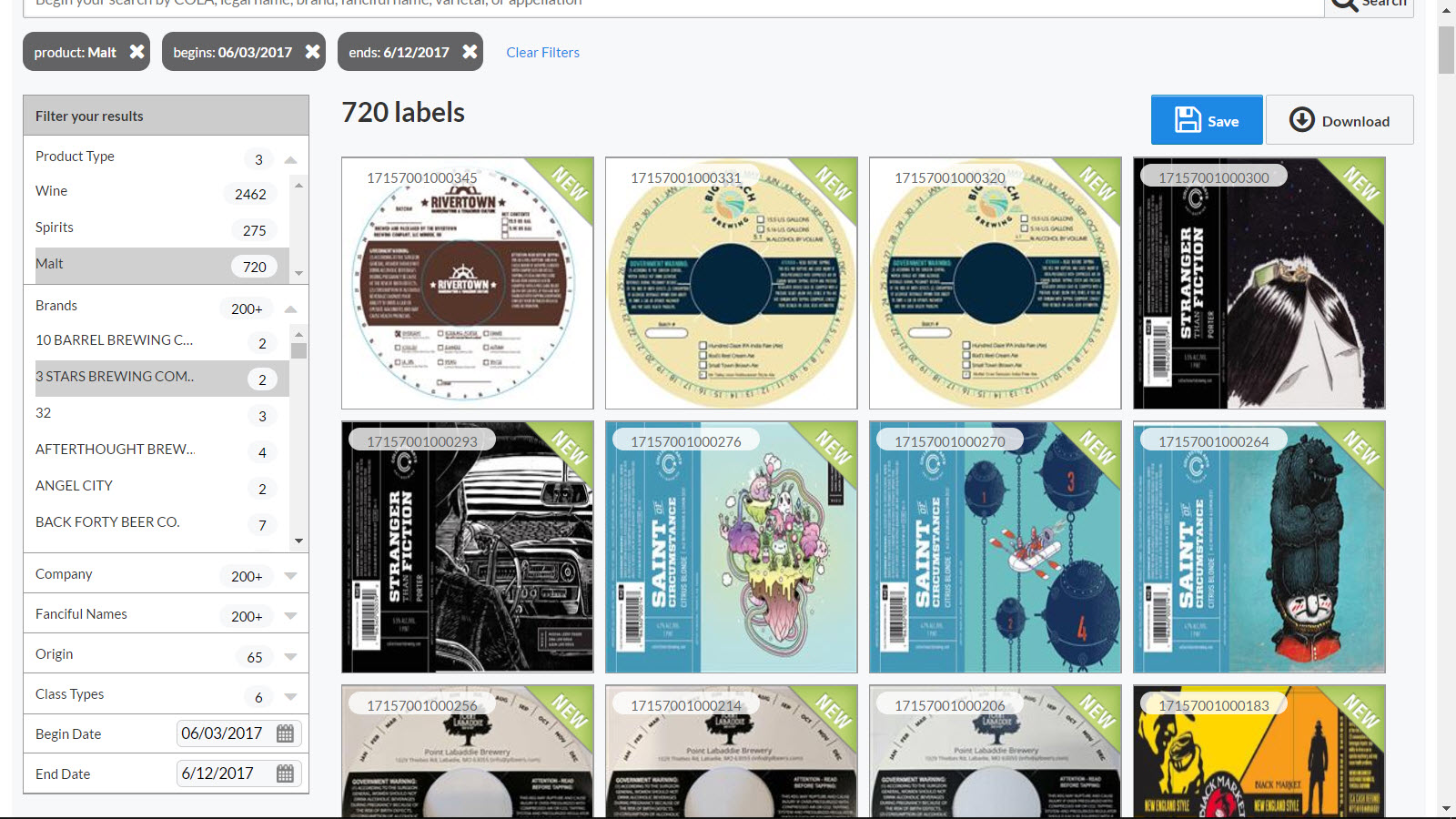

This jumped out at me when looking at beer approvals from a recent 10 day period in 2017. I saw no less than 720 new brands/approvals — just for beer — in this small and recent time period. Most of them seem like just about the opposite of Budweiser and Coors.

By contrast, I looked at the same 10 day period, 10 years prior. The landscape is altogether different. In the 2007 period I see a relatively puny 175 approvals. The overwhelming preponderance of those labels are from big or very big companies: Miller, A-B, Sam Adams.*

In the 2017 period I see almost no mega-brews. If this is not a revolution, it seems to be a radical change at least, in just half a generation or less.

Amazon has well proven they can stock and sell a lot of books and other SKUs, without losing a bunch of money. Let’s see how they do with a few hundred thousand beers.