Last week’s U.S. Supreme Court decision, Pom v. Coca-Cola, is not just about juice. It has massive implications for small brewers, big distillers and all other alcohol beverage marketers. It shows that TTB rules and other agency rules set a floor, not a ceiling, on how companies need to market their products. It shows that the government is only a part of the web of review, in concert with competitors. Just as we predicted that Pom would win this case, we now predict that some alcohol beverage companies will soon take legal action against others, even though such cases, other than trademark cases, were very rare in the past 50 years.

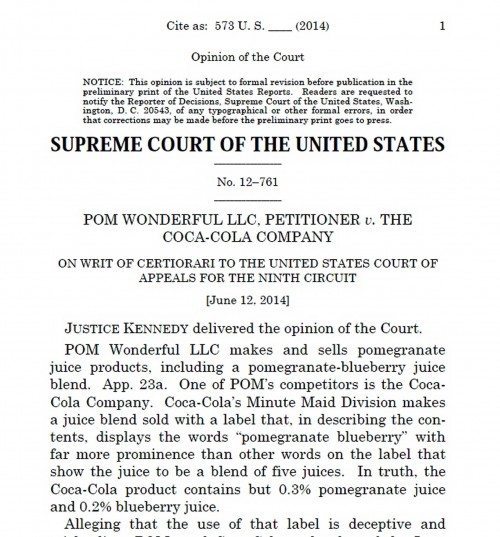

It was bad enough for Coke when Pom called out Coke for going quite a bit too far in posing its apple juice as pomegranate juice. It got even worse when various Supreme Court Justices suggested, orally, that Coke was trying to trick people. And on June 12, 2014 it got even worse, when the Supreme Court unanimously disagreed with Coke’s position. In Pom v. Coca-Cola, the Court said, if there is trickery on food labels, and it hurts a competitor, of course they can do something about it, even if FDA (for whatever reason) does not.

Pom and the Supreme Court have made it clear that one company can go after another for dubious labeling, and the government no longer has all the authority in this area.

The Court said, rather than the Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act (FDCA) knocking out the Lanham Act, the two Acts can happily coexist, complement each other, and provide synergy. The former protects consumers as to health and safety. The latter protects competitors as to commercial interests.

We have lots more coverage of this important case, and the background, in this post from earlier this year.

Coke went astray fairly early in the multi-year litigation, trying to invent a theory under which FDA “approved” the label at issue. FDA did no such thing. To approve is an act, and FDA’s posture here was the opposite of an act. FDA did not condone, approve or disapprove the label at issue. Perhaps FDA was busy with many other pressing concerns, or it was a gray area. This is in stark contrast to how TTB handles most labels — with a rigorous, case-by-case, and explicit pre-market approval regime. To say that FDA approved the Minute Maid label is like Donald Trump getting one $500 haircut per week, every week, calling it a business expense and taking an IRS deduction for 10 years — then saying the IRS approves of his hairstyle and his deduction. The IRS would, of course, have done no such thing. Rather, it would be the case that the IRS, simply, had so far refrained from any adverse action. To use the terms in the opinion, there is a difference between approving something and merely tolerating it.

There are not a lot of juicy quotes in the opinion, but the case does have massive implications. The Court noted, in a realistic way, that:

FDA … does not have the same perspective or expertise in assessing market dynamics that day-to-day competitors possess. Competitors who manufacture or distribute products have detailed knowledge regarding how consumers rely upon certain sales and marketing strategies. Their awareness of unfair competition practices may be far more immediate and accurate than that of agency rulemakers and regulators. Lanham Act suits draw upon this market expertise by empowering private parties to sue competitors to protect their interests on a case-by-case basis.

It is very refreshing to see Washington give some credit to those who work in an industry long-term, every day. The huge implications of this case would seem to be:

- A massive shift of enforcement authority, from bureaucrats in Washington, to private parties all around the world. Professor John Duffy noted: “A second important point about POM is that the reasoning in the decision shows the Supreme Court’s increasingly ambivalent approach to administrative regulation. More than a century ago, administrative agencies were often cast in nearly heroic terms; they were thought to be wise experts who could bring intelligent, centralized regulation to remedy the abusive marketplace tactics. In yesterday’s decision, however, the Court shows just how little is left of that notion.” Duffy nails it, saying: “It is … hard not to think that some of the reasoning in this case reflects a new skepticism – or perhaps it should be described as a healthy realism – about the capabilities of administrative agencies.”

- Justice Roberts, in the oral arguments, actually said, in reference to misleading labels: “What does the FDA know about that? I mean, I would understand if it was the FTC or something like that, but I don’t know that the FDA has any expertise in terms of consumer confusion apart from any health issues.”

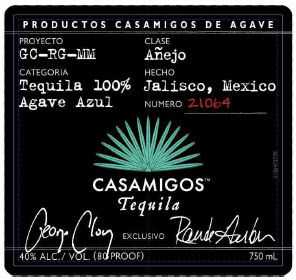

- The ready ability of Coke to police Pepsi’s business practices, Bud to police Coors, Gallo to police other wine companies, Bacardi to regulate Diageo — on and on. Not only can the big regulate the big, but the small can regulate the big and vice versa. It could be a free-for-all. Duffy explained that this case, along with another: “is almost certain to produce a significant expansion in competitors bringing Lanham Act claims against each other over false or misleading statements.”

- Even more, this means little craft brewers and distillers can go after big guys with a claim that: “you are BS’ing about craft, and it hurts us.”

- An advertising law expert said: “It opens the floodgates to increased litigation. The message to marketers is now that compliance with the FDA is only a first step and is by no means insurance against other types of claims.”

- This will give us a bit of a taste of what libertarian-style government might look like, and a bit of relief from command-and-control government, perhaps.

- Even though there is affirmative pre-market approval for alcohol beverages, and this is not the case for most foods and other beverages, it would seem that the same basic principles apply. It would seem that the FAA Act was likewise not intended to impair or preclude the Lanham Act.

- On behalf of food clients, food lawyers now get to serve as mini-FDAs, and private TTB lawyers have been deputized to serve as mini-TTBs (on behalf of any aggrieved beverage company clients).

- This makes it easy for TTB and FDA to deflect many complaints, and remind the aggrieved that they have a ready means for self-help.

- After many decades to the contrary it may turn out that the federal food and beverage laws are a floor, rather than a ceiling. CSPI said: “The Court recognized that companies don’t have a safe haven from being sued for deception just by complying with FDA’s minimal regulations.”

It will be ironic indeed when a competing food company goes after Pom. But Pom seems more than able to protect itself and I have rarely seen a better example of a company being on the defensive, after the various FTC inquiries — and turning it into such a major victory. There should be a cliche about turning bitter fruits into profitable fruit juices.

Leave a Reply