There are something like 25 pending lawsuits, about whether various alcohol beverage labels are misleading.

There are something like 25 pending lawsuits, about whether various alcohol beverage labels are misleading.

Right there, that should tell you there is not much safe harbor, even though every one of those labels was federally approved, pre-market. Most of the labels were approved many times over many years.

Of course, the first refuge of every defendant is to argue that heavens no, the label can’t possibly be misleading, because the mighty TTB examined and approved it, after all.

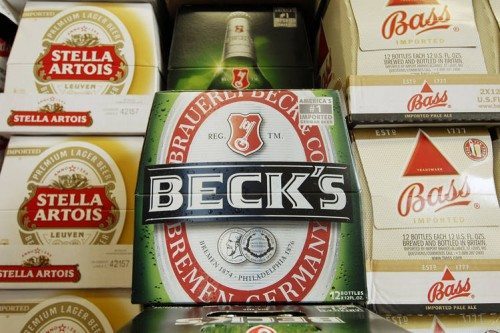

The very recent Beck’s settlement should put this trite notion to rest. Over and over TTB said yeah the Beck’s label is fine, even though it has a bunch of references to Germany and the brand’s history, and even though the beer has been made in the U.S. for many years now. The court approved the settlement on October 20, 2015.

In my opinion, the harbor should not be any safer than the review is rigorous. To the extent TTB carefully focused on the specific issue in controversy, and ruled on it, according to rigorous standards, that would be a different story. But, by contrast, a quick review and a shot from the hip should not a safe harbor make. I don’t mean to be too critical of TTB or A-B. The same parties can also provide a good example of the very opposite phenomenon, where the review is more probing, and the harbor stood up as safe. The Lime-A-Rita case shows this other side of the coin. In the Lime-A-Rita case, the plaintiffs said the label is deceptive because it refers to (Bud) Light, when in fact the product is loaded with sweeteners and is no paragon of lightness. But A-B beat back this challenge, and rightly so, because in this instance TTB did have good, solid, narrow, relevant, rigorous standards, duly applied by TTB and duly complied with by A-B, and so eureka the many TTB approvals did in fact provide a warm and cozy safe harbor.

In my opinion, the harbor should not be any safer than the review is rigorous. To the extent TTB carefully focused on the specific issue in controversy, and ruled on it, according to rigorous standards, that would be a different story. But, by contrast, a quick review and a shot from the hip should not a safe harbor make. I don’t mean to be too critical of TTB or A-B. The same parties can also provide a good example of the very opposite phenomenon, where the review is more probing, and the harbor stood up as safe. The Lime-A-Rita case shows this other side of the coin. In the Lime-A-Rita case, the plaintiffs said the label is deceptive because it refers to (Bud) Light, when in fact the product is loaded with sweeteners and is no paragon of lightness. But A-B beat back this challenge, and rightly so, because in this instance TTB did have good, solid, narrow, relevant, rigorous standards, duly applied by TTB and duly complied with by A-B, and so eureka the many TTB approvals did in fact provide a warm and cozy safe harbor.

TTB has narrow, careful rules around many terms such as “straight,” “estate bottled,” chardonnay, Napa Valley, “Late Harvest.” Thus, these are the types of terms that should provide a safe harbor (when properly used and approved, according to the same rules). But, by contrast, TTB nor anyone else has good, solid, rigorous rules around terms such as craft, handmade, handcrafted, small batch, reserve, etc. — and so it is much less clear that a safe harbor should apply. It is true that the terms could be puff, in the absence of such rules, but who ever said it is either black or white, puff or not, all or nothing? Surely there are some terms somewhere in the middle, neither pure opinion nor hard fact. I do agree that many label terms do gravitate toward one pole or the other, and I do agree that such terms should be protected, as either puff or within a safe harbor. But we still need a good plan for the terms somewhere in the middle. Maybe TTB should develop and apply some rigorous rules on such. Or maybe the companies that want to use them should explain what they mean by them, to put them in a comprehensible context.

One more example should make the point. Templeton Rye, like Beck’s, Bass, Kirin and many others, also of course had TTB-approved labels. This did not stop the lawsuits or provide any safe harbor. If there were a safe harbor to be found, anywhere near these controversies, the defense lawyers certainly would have found it.

The Beck’s case underscores one other quandary. It is hard for me to understand how it can be a good, long-term business plan, to take the Beck’s brand, known for being German if nothing else, and blur the life out of it by making it elsewhere. The penalty within the lawsuit is something like $28 million, but the obliteration of the Beck’s identity seems far more expensive in the long term. A-B paid a couple billion dollars for the brand in 2012. I can only assume it is short-term, quarter-to-quarter, propping up the numbers, Wall Street thinking, designed to enrich the near-term stakeholders, at the expense of those who arrive at the punch bowl later.

While lawyers will argue anything, for a fee, on the TTB application, right above the signature line, is a simple statement. “Under the penalties of perjury, I declare; that all statements appearing on this application are true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief; and, that the representations on the labels attached to this form, including supplemental documents, truly and correctly represent the content of the containers to which these labels will be applied. I also certify that I have read, understood and complied with the conditions and instructions which are attached to an original TTB F5100.31, Certificate/Exemption of Label/Bottle

Approval.”

When suppliers knowingly submit false and/or misleading COLA applications they must be held responsible or this system will have less credibility than the misleading labels themselves.

If, on the other hand, it was the obligation of the TTB to investigate and verify every letter of every word on every COLA application, suppliers would be up in arms because it would take years to get even the simplest COLA approved and no one, with the exceptions of lawyers, would like that scenario.

But where is anything close to perjury in the Beck’s case?

While, I’m not a lawyer, and don’t play one on the internet, my comment was more to the point of safe harbor claims by spirit producers.

Although it may not be precisely ‘perjury’ there appears to be little doubt that the Beck’s label was designed to mislead consumers into thinking they were buying an imported beer even though the label was approved by the TTB. Proving intent is always difficult, despite the facts.

How quickly they forget!….recall the Lowenbrau fiasco in the mid ’70s when Miller Brewing acquired the North American rights to the brand and began brewing it in the U.S…..I lived in Milwaukee at that time when the nosedive began.