Earlier this week Robert had the pleasure of presenting a speech at the American Distilling Institute conference in Seattle. The speech was entitled “Needs Correction: 9 Common Label & Formula Controversies for Spirits at TTB.” A copy of the PowerPoint is here. The speech covered common Needs Correction issues such as proper class/type statements for moonshine labels, when age statements are required and prohibited, and the term “craft.” On the formula side, the speech covered when a formula approval is and is not required, and common issues that can make a fairly slow system even slower.

Wine Growlers

Environmentally-conscious and corkscrew-phobic wine lovers alike will be thrilled to hear that TTB issued a ruling on March 11, 2014, allowing the filling of wine growlers by TTB-licensed tax-paid wine bottling houses (“TPWBH”). The ruling is in response to a new Washington state law allowing state-licensed wineries to sell wine off-site in kegs or “sanitary containers” (i.e., growlers) for off-premise consumption. Oregon passed a similar law in April 2013.

These laws are particularly helpful to wineries that operate both a production facility and a separate tasting room, allowing them to fill growlers for off-premise consumption at either location. The TTB ruling is somewhat less helpful to wine retailers, requiring that they go to the extra trouble of becoming TPWBH-licensed and comply with label and recordkeeping requirements.

Some wine retailers complain that it is unfair to not allow non-TPBH wine shops to sell growler fills to-go, since beer shops currently enjoy that privilege. TTB explains, the Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”) “has very specific requirements regarding the bottling of taxpaid wine. Section 5352 of the IRC requires any person who bottles, packages, or repackages taxpaid wine to first apply for and receive permission to operate as a taxpaid wine bottling house. There is no analogous provision with respect to beer.” The current TTB ruling interprets growler filling as bottling or packing and, therefore, restricted to TPWBH-licensed vendors.

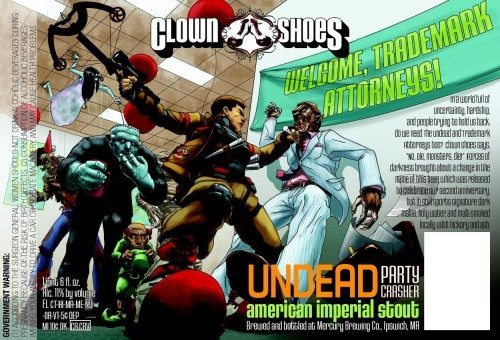

Don't Mess with a Vampire

I am thinking this may be the best label ever, about lawyers. If I am not mistaken, that is a garden-variety lawyer, right below “Welcome, Trademark Attorneys!” and right above the briefcase. The lawyer just happens to be wearing a pink shirt, white suit, and closely resembles a werewolf.

It all started when Clown Shoes beer company got label approval for a Vampire Slayer beer in 2011. It is important to note that this beer claims to be made with “holy water” and “vampire killing stakes.”

In short order, the company that controls various VAMPIRE-related trademarks, pounced, and pushed Clown Shoes to cease and desist from using VAMPIRE terminology. Here is an example of a recent label approval, for a wine marketed by the company that controls the VAMPIRE mark. Clown Shoes explains:

Vampire Brands and TI Beverage Group, connected companies out of California that primarily market vampire themed wine, were suing us. They came to market six months after Vampire Slayer began distribution with a beer made in Belgium called Vampire Pale Ale, but they filed a trademark application prior to our distribution. Their position was that our use of the name Vampire Slayer was harming their ability to sell Vampire Pale Ale, literally costing them money.

Clown Shoes was not amused, and expressed its dismay on the label above. In addition to the not-so-flattering imagery, the label also says: “Do we need the undead and trademark attorneys too? Clown Shoes says ‘No, Die Monsters, Die!’ Forces of darkness brought about a change in the name of this beer. …” Clown Shoes caved in because:

we felt that we stood an excellent chance of winning a court battle. Then we found out that litigation could cost between $300,000 to $400,000. … Ummmm… that sounds like stabbing ourselves in the face to cure foot pain. … A settlement, the terms of which I am not at liberty to disclose, was reached with [Vampire Brands] that licenses Clown Shoes to use the name Vampire Slayer. I can say that based on all factors, the Vampire Slayer name will soon be discontinued, despite the licensing agreement.

All of this just goes to show that nobody should mess with vampires, going into a trademark dispute without some protection, or the attorney at Vampire Brands. A good article about the dispute is here. Volokh has some other law-related labels here. And a good, recent, other lawyer-related label is right here.

NJ Law Journal

The New Jersey Law Journal recently featured Lehrman Beverage Law in a story about the growth of craft beer producers, craft spirits producers, and the law firms that have sprung up to support them. An excerpt of the story is here (the full version is here and requires registration). We are pleased to report, further, that our firm typically has at least five or six professionals working directly on alcohol beverage matters in a typical day. This particular article highlights Dan, who is a trademark and beer lawyer; John, who is an avid home brewer and handles a range of alcohol beverage issues; and Robert (who is not sure whether to be thrilled or mortified as he enters his 27th year handling legal issues for beer, wine and spirits companies around the world).

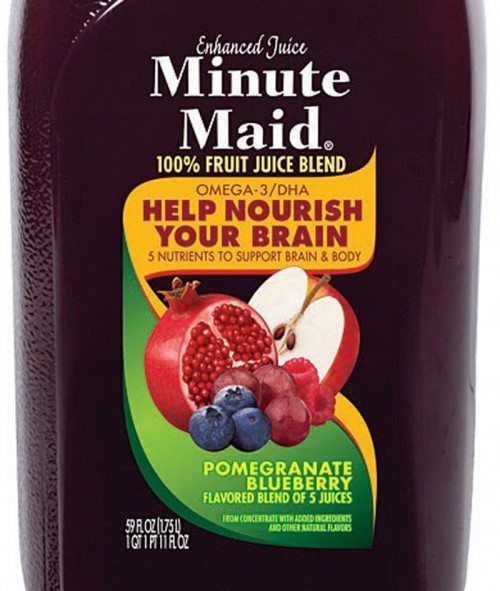

Pom v. Coke, Battle of the Misleading Fruits

Pom’s superfamous lawyer argued:

This is a classic false advertising case. Pom and Coca-Cola compete directly in the market for pomegranate juices. Pom sells juices that—as purchasers would naturally expect—overwhelmingly contain actual pomegranate juice, which is sought by healthconscious consumers. Pom’s products include a pomegranate-blueberry juice. Coca-Cola sells and aggressively markets its competing “POMEGRANATE BLUEBERRY” juice, which it colors a deep purple and sells with a label containing a large image of each fruit. … Coca-Cola’s misleading label causes consumers to believe that the juice actually contains significant amounts of those fruits when in fact it contains only trivial amounts: 0.3% pomegranate juice and 0.2% blueberry juice. … Pom introduced survey evidence showing that consumers are in fact seriously misled.

Pom also quotes a key part of the government’s brief: “Further, the ‘FDA does not approve juice labels, and its failure to initiate an enforcement action cannot be construed as such an approval.'” Other juicy tidbits courtesy of Pom include: FDA and the FDC Act “sets a ‘floor’—not a ceiling—on federal regulation of labels.” Pom explains the sweeping importance of this case, and why it is so ripe for review:

Even if it were limited to food products, the ruling below grants tens of thousands of food and juice producers sweeping immunity with respect to countless products from liability under the Lanham Act for even knowingly misleading consumers. … The government recognizes that the court’s “deference to FDA’s available but unexercised authority would arguably preclude a Lanham Act challenge to the label of any food,” including “the many foods that FDA’s regulations do not specifically address at all.” … As the GAO has confirmed, the FDA “generally does not address misleading food labeling because it lacks the resources to conduct the substantive, empirical research on consumer perceptions.'”

By contrast, Coke not surprisingly argues “the FDA has adequate resources to regulate the content of food and juice labels.” Coke further argues:

whether a multi-fruit juice name or label is deceptive is not only within the FDA’s expertise, but is a topic that the FDA has already addressed in detailed and specific regulations. … As the United States correctly observes, the regulation “reflect[s] the agency’s balance of competing considerations in a specific setting that could easily be upset by the intrusion of a general private remedy such as that provided under Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act.”

Getting deep into the nitty gritty of the labels at issue and the rules, Coke proudly proclaims “Here, the letters ‘FLAVORED BLEND OF 5 JUICES’ comply with this specific regulation because, as is clear from the image …, they are more than one-half the height of the words ‘POMEGRANATE BLUEBERRY.'” Coke claims it is a big (“hyperbolic”) exaggeration to say FDA lacks sufficient resources to regulate food labels.

If Pom wins this battle, it will seem to be another sign that the government, step by step, as it gains powers in some areas, continues to relinquish power in other areas, to allow large segments of statutory and agency mandates to be effectively privatized (or libertarianized). For example, as here, Pom and other Coke competitors would become the reviewers of Coke’s labels every bit as much or more compared to what FDA might have done in the past. This case could have enormous implications far beyond FDA labels, and could extend all the way over to TTB labels, TTB formulas, excise taxes, TTB permits, to almost every area that alcohol beverage regulators have firmly controlled in the past. In other news, this case provides a wonderful forum for Pom to beat up on Coke, and remind everyone that Pom has more juice, up and down the U.S. court system, year after year (since at least 2008). I wonder how the cost of this lawsuit compares to or relates to an old-fashioned ad campaign in the paid media.

From our perspective, working with thousands of labels and hundreds of such questions (from the trivial to the weighty) on a yearly basis (as opposed to an appellate litigator or a judge dealing with this from time to time when it flares up big) it seems clear that such tricky questions will inevitably get “litigated.” The only question is whether they will get litigated in an agency proceeding (as has been common in the past), the media, amongst lawyers battling apart from a court or agency proceeding, or in the courts (as was fairly rare in the past). To the extent that Pom wins, we can expect a huge shift from the first to the last.

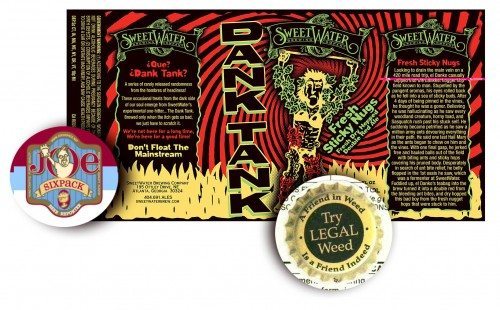

Beer, Pot and the Government

With this month’s ballyhooed legalization of marijuana in Colorado, some beer makers are adding playful drug references to their brand names and labels, and regulators can do little to censor them.

Label oversight, a quirky if contentious area of federal alcohol law, has confounded breweries for years with often capricious standards that bear little on consumer protection.

Federal law, for example, oddly prohibits the use of coats of arms or wording that promises ‘pre-war strength,’ whatever that means.

Mr. Russell (aka Joe) also helped educate me that a safety meeting is not necessarily boring and dire:

Yes, there are limits. Dark Horse Brewing, in Michigan, lost its bid for Smells Like Weed IPA, though its hops, in fact, smell like pot. The name was later changed to Smells Like A Safety Meeting IPA. (A ‘safety meeting’ is slang for taking a break on the job to light up a doober.)

But expect to see fewer of those objections as more states move toward legalization.

Joe Sixpack has at least 16 label examples here and here.