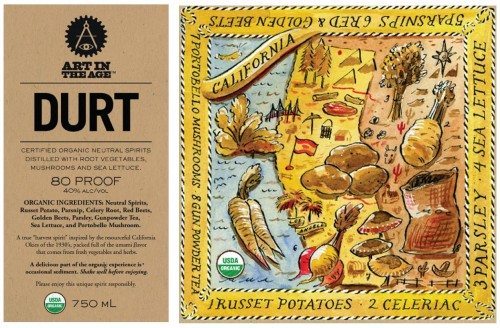

This one caught my eye as quite a bit unusual. It is spirits with added mushrooms, sea lettuce, parsnips and other root vegetables. It is Durt-brand spirits, produced by Melkon Khosrovian, and is not to be confused with Root-brand spirits. I don’t see much on the label or on the web to suggest what it tastes like, or how it is to be used, except where the label says “packed full of the umami flavor.” Wikipedia explains that umami is one of the five basic tastes along with salty, sweet, sour, and bitter, and “can be described as a pleasant ‘brothy’ or ‘meaty’ taste with a long lasting, mouthwatering and coating sensation over the tongue.”

Not to be left out of the umami-fest, here is a beer with plenty of umami, and a wine/sake “bursting with umami goodness.”

Malort

On a long drive recently, NPR held up Malort as the gold standard for what tastes bad, as if this had been firmly decided. So, after hearing about this concoction over the years, it was time to see what all the revulsion was about. The New York Times said “The taste has been compared — by advocates and detractors alike — to rubbing alcohol, bile, gasoline, car wax, tires and paint thinner.” One “Malort face” is here, a collection is here (and NPR’s audio reaction is here).

Malort is Swedish for wormwood, a key ingredient of this liqueur. The same mischievous plant (also known as Artemisia absinthium) also provides a key ingredient and the name for absinthe and vermouth. Recent Jeppson’s labels do not mention the following, but the writing seemed so distinctive that I wanted to capture it before it recedes further into the past:

Most first-time drinkers of Jeppson Malort reject our liquor. Its strong, sharp taste is not for everyone. Our liquor is rugged and unrelenting (even brutal) to the palate. During almost 60 years of American distribution, we found only 1 out of 49 men will drink Jeppson Malort. During the lifetime of our founder, Carl Jeppson was apt to say, “My Malort is produced for that unique group of drinkers who disdain light flavor or neutral spirits.” It is not possible to forget our two-fisted liquor. The taste just lingers and lasts – seemingly forever. The first shot is hard to swallow! PERSERVERE [sic]. Make it past two “shock-glasses” and with the third you could be ours…forever.

I am not sure if it sounds more like a sales pitch or a threat. Other than the Wikipedia article, I could not find much to verify that this text appeared on labels. Apart from the shock value of this product, as per usual, legal issues abound. First, I wonder how this comes to be classified as a beverage (subject to taxing and licensing as an alcohol beverage). If this is not non-beverage or unfit for beverage purposes, it starts to get really difficult to make this distinction (as between potable and non-potable), so crucial to much of the law around alcohol beverages. Malort may underscore that it’s okay for one purveyor to elect to be regulated as a beverage, even when the liquid tastes awful, and even though it would not be okay for another purveyor (of drinks with “rugged and unrelenting” flavors) to capriciously elect to be regulated as non-beverage.

A second law-related issue arises from the ownership of this brand. Carl Jeppson was an immigrant from Sweden and brought Malort to the U.S. during the Prohibition era. Before Jeppson’s death in 1949, he sold the recipe to a Chicago lawyer, and he left the company to his secretary, Patricia Gabelick. As of 2012, Ms. Gabelick was a “69-year-old retired secretary who runs the company out of her condo on Lake Shore Drive” in Chicago. The Wall Street Journal explained:

sales climbed last year by more than 80% from just a few years ago to 23,500 bottles, with annual revenue of more than $170,000. … Ms. Gabelick seems a bit baffled by the interest in Malört, which was a hobby for her boss, George Brode, a Chicago lawyer who left the company and its one product to her when he died in 1999. … “All my life I wish George had made a product I could drink,” she says. … Jeppson’s Malört got its start when Mr. Brode landed one of Chicago’s first liquor licenses after the repeal of Prohibition in 1933. He added Malört to his stable of liquors when approached by Carl Jeppson, who had a recipe for a spirit favored by the city’s Swedish immigrant population. Mr. Brode eventually exited the liquor business for a career as a lawyer, but kept Jeppson’s Malört.

Even if this blog can’t help you with what to drink this holiday season, we wanted to do our part toward informing you what not to drink.

Beer Pong and Alcohol Beverage Patent News

We try to stay on the lookout for good and serious patents related to alcohol beverages. A few good ones are here. Today, we wanted to take a look at the ones that seem even less serious and a bit more, frothy. Dan Christopherson is an experienced trademark lawyer, and a registered patent lawyer, and Dan located a few good examples as below. Dan explained, “With all of the bad press coming out lately reporting craft brewers suing each other for allegedly infringing their intellectual property rights, we thought it might be a good idea to try to lighten the mood a bit.” With that in mind, here are a few humorous beer-related patent applications Dan came across:

“Tooth Protector for Beverage Bottle and Beverage Bottle Enclosure” – US Patent Application No. 2012/0225166 by Krag David Hopps. I get as excited as the next guy/girl when I crack open a bottle of craft beer. That said, I have, to date, been able to temper my excitement enough to avoid crashing into and injuring my incisors with a beer bottle. Unfortunately for those individuals who have not shared in my good fortune, to quote Mr. Hopps, “No device has heretofore been available to protect a person’s teeth when he/she is drinking from a glass bottle.” This device, shown on the left, literally shields a beer drinker’s teeth from a beer bottle while drinking from the bottle. Mr. Hopps’ invention is sure to bring us into the golden age of bottle consumption safety. Good news for those of you with drinking problems.

- “Chewing gum with containing ethanol flavors“ – US Patent Application No. 2013/0034625 by David L. Ross. It is truly unfortunate that this patent application apparently does not include any images because I would love to see what this invention looks like. Mr. Ross has invented a beer flavored gum wrapped in a beer mug/bottle/keg shaped packaging “that encloses between 0.01 milliliters and 2 milliliters of alcoholic beverage [ethanol] in at least one cavity inside the gum.” Our rough calculations show that you’d have to chew at least 18 pieces of gum to get about the same alcohol content as a single bottle of a popular macrobrew. Better a sore jaw than a sore liver, I guess.

- “Netting system for drinking games” – US Patent Application No. 20120071278 by Andrew Mansfield. We agree with Mr. Mansfield’s sentiment that “a need exists for a cheap, easy to manufacture and an easy to use system that prevents ping pong balls from hitting the surrounding floor during game play.” As Mr. Mansfield points out, the previous attempt to clean up these games by providing wash cups to clean playing balls before throwing them into an opponents’ beer glass “is inefficient and often ineffective as the wash cups become dirty and contaminated from repeated contact with dirty ping pong balls as the game progresses. In addition, research has shown that the wash cups still hold bacteria, such as E. coli.” Without going through Mr. Mansfield’s undoubtedly comprehensive research results, we are relieved to hear that hygiene-conscious partygoers will no longer be left out of beer pong games.

“Beer Pong Table with Cooling System” United States Patent No. 8,235,389, issued to Big Dog Pong, LLC. Big Dog Pong also took great strides to improve the great sport of Beer Pong with this invention. A true visionary, they recognize that playing beer pong on kitchen tables, closet doors, and other homemade tables can “unfairly affect the game” and that “beverages may become warm during play.” Big Dog Pong accomplishes all of this by placing a series of cooling areas into the table top surface of a standardized beer pong table.

We hope this post inspires you toward some frivolous or not so frivolous inventions of your own, or at least provides a welcome respite from the serious side of law, business, and intellectual property.

Wine Trademarks in China

All the while you tend your vines, and the U.S. market for the fruits thereof, your precious brand names may be vulnerable to poaching, in the world’s most populous country. Lindsey Zahn points out the risks in a recent article in the Cornell International Law Journal Online. The article is entitled “No Wine-ing: The Story of Wine Companies and Trademark in China” and it was published on November 4, 2013. It points out the risks and opportunities, and provides a good overview of how China treats wine trademarks, and how that differs from the U.S. system. Lindsey is a lawyer specializing in wine law and food law, and she is a frequent writer on such issues at winelawonreserve.com.

In the article, Lindsey explains:

China follows a “first-to-file” rule for trademark registration. This means that the first person to file a trademark application with the China Trademark Office (“CTMO”) is usually granted the registration rights. Prior use of a mark in commerce generally affords little or no protection to a trademark applicant in China. By contrast, the United States Patent and Trademark Office considers whether the applicant is the first to use or intends to use the mark in commerce.

If a business even contemplates entering the Chinese market, it is generally recommended that a trademark application be filed before any product or service is present in China’s market. Failure to file trademark registration can allow third parties—referred to as brand “squatters”—to register the mark. This presents many problems: the prior registration of the mark can block the true brand owner from registration or force the owner to change its name to enter the Chinese market. Other times, a brand owner is forced to pay exorbitant fees to the third party registrant in order to procure the rights to the mark.

This is an important and timely topic, and the rest of the article is here. TTB has lots of good information about alcohol beverage law in China, here.

Of DSS, SOC and LabelVision

Well here I sit, writing on day 15 of the shutdown. All the government stuff I need (such as COLAs Online) is unavailable. Thank goodness that all the private stuff is available. It takes a lot of public and private resources to make this blog go. That is, on the private side, I need my web server, my ISP, my WordPress, Google, a bit of AC power, etc.

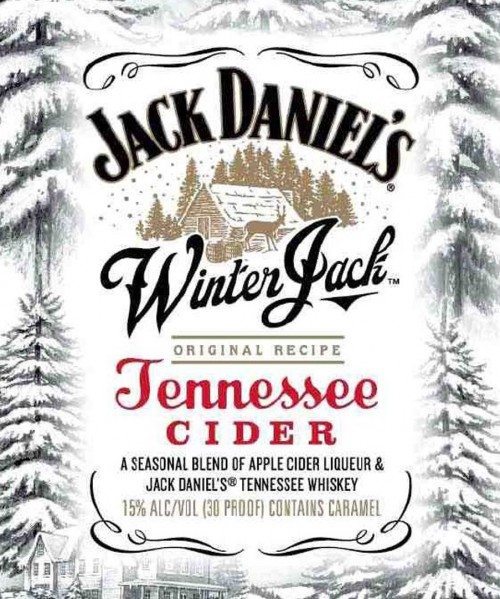

Increasingly, I also need my LabelVision. LabelVision is a tremendous resource, provided by the people at ShipCompliant. It provides various ways to scour TTB’s label database, even when TTB’s systems are down. LabelVision enabled me to quickly find the WinterJack COLA as above. To find this label, my other and much less appealing options would have been to wait until TTB re-opens someday, or jump in the car and drive around until I find this new product.

I had a sudden need to look at this Tennessee Cider label in order to explore what is new and current in distilled spirits specialty (“DSS”) labeling, and the statements of composition (“SOC”) that go along with this category of spirits. To recap, where you have a common type, set out in the regulations, it is sufficient to mention simply VODKA or RUM or TEQUILA or WHISKEY. But where you have something more like miscellany, it is necessary to provide, on the front label, a “statement of composition.” This needs to appear near the “fanciful name” (and “brand name”) — and needs to match the SOC as suggested on the approved formula (formula approval is required for all DSS products). Most suggested SOCs have the alcohol base, then flavors, then colors, with very little extraneous matter. And so, the “normalized” SOC, here, would be LIQUEUR, WHISKEY, CARAMEL COLOR. Not too enticing.

So, with plenty of marketing prowess, the mighty Jack Daniel Distillery has substantially rearranged the various terms. Even the smallest changes (such as changing WITH NATURAL FLAVOR to WITH NATURAL FLAVORS) can cause delays, needs correction notices and rejections. Here, it seems Brown-Forman changed what would have been the TTB-suggested SOC, to add a whole lot of puff. All these words got added to the SOC: A, SEASONAL, BLEND, OF, APPLE, CIDER, JACK, DANIEL’S®, TENNESSEE. All these words got removed (from the SOC): CARAMEL COLOR. That is, the most-probably-suggested-SOC and the approved-label’s-SOC do not have a whole lot in common. And yet the label got approved.

I am not trying to suggest that there is anything wrong with the label or the SOC at issue. Instead I am using this label as an example of how the seemingly simple requirement, to put an SOC on the front, can raise many legal issues. Should the caramel be shown in the same font and color as the remainder of the SOC? With the caramel moved a line below the SOC, would it be ok to move it a bit more, such as to the back label? At what point does the puff, in the SOC, go too far and crowd out and obscure the true SOC? Could Brown-Forman add the caramel to the whiskey component, rather than the end product, in order to de-emphasize or avoid label references to color? For every approval like this, with a “creative” SOC, how many times did TTB press for an SOC that much more closely matches what is suggested on the formula approval?

TTB Shutdown?

Updates

Day 1, 10/1/2013, 6:30 am ET: TTB is shut down for the most part but at least COLAs Online and Formulas Online seem to be functioning normally (to retrieve approvals, etc.). Permits Online and COLA Registry seem to be working normally too.

Day 1, 8:55 am ET: this notice posted to the front of ttb.gov. No updated notice on the voicemail system.

Day 1, 9:10 am ET: this notice paints a pretty dire picture. It says: “there will be no access to TTB’s eGovernment applications including, but not limited to, Permits Online, Formulas Online, and COLAs online.” It further says: “TTB has directed employees NOT to report to work and they are prohibited by federal law from volunteering their services during a lapse in appropriations.” If it’s really true, that the websites (such as CO, PONL and FONL) will be shut down, I am happy that we went to the bother over many years to get a copy of every one of tens of thousands of approvals we have handled. It was a lot of work but we knew it was just a matter of time before one calamity or another came to pass.

Day 1, 9:15 am ET: I am happy to report that, despite the 9:10 message above, the websites seems to be operating normally. If you can see this COLA, they still are. If I may editorialize just a bit (more) — how very banana republic when the government is shut and we know not when it may resume, but have to wait for it anyway to do just about anything.

Day 1, 9:30 am ET: sites now off, as here. This is going to get ugly (uglier).

Day 2, 10/2/2013, 8:30 am ET: this is nuts. It is close to impossible for many alcohol beverage companies to get oxygen or sunlight. As I peruse the list of things most adversely affected, such as national parks, it is tough to find areas more adversely affected than beer, wine and spirits. (For example, whereas the adverse impact on a new flavored wine at 8% is almost total, the impact on the same product at 6% would be nil.) It is particularly egregious to set up a system where most every move must be slowly and painstakingly reviewed and approved — then withhold such review and approval, indefinitely. In the case of parks, the eager vacationer can always divert to Disney, the beach, or a local bar. Many beverage companies have no such options, but to wilt. Want to add some coriander to that beer? No can do. Until someday in the far-off future, after the parties decide to talk, the government perhaps reopens, the backlog clears, and eventually, at best, it goes back to something resembling the pitifully slow system of the past where it can take well more than six months to jump through enough hoops to add that coriander to that beer. Need to take something out of that flavored vodka? You can’t do that either. So long as there is a realistic possibility that things like the above can happen, the rules ought to provide backup systems. Without faulting any particular agency or party, I fault a system where the regulated parties are held to high standards and the government is held to approximately no standards at all.

Day 3, 10/3/2013, 7 am ET: how long until the very best people at TTB start to bail out, and the prophecies of the most ardent government detractors get fulfilled?

Day 6, 10/6/2013: things will be jammed up for months, at best.

Day 17, 10/17/2013: TTB finally comes back to life. Google has more than 26,000 items about the shutdown’s impact on beer alone.

Will TTB shut down this week and if so how painful will it be? And who will get the blame?

As of this writing (2 pm ET on the last day of September) a shutdown looks all but certain. The New York Times says the only big question is who will get the blame. I don’t see much on TTB’s website about this yet, but Google helpfully (as always?) turns up this Shutdown Plan.

The key points in the Plan are:

- Once appropriations have lapsed, the shutdown will encompass all of TTB’s core mission business (with some exceptions, such as things essential for safety of human life, and otherwise funded Puerto Rico functions)

- All normal operations will cease (with few exceptions)

- These important things will not continue: processing of permits, certificates of label approval, and formulas

- Only about 35 of 483 employees (and about 135 contractors) are essential and can work during the shutdown

Many things were jammed up before this big piece of other than good news so it’s going to be brutal and slow for quite some time. If you did not start seeking approvals long ago, it sure looks like you will be regretting it any moment.

It is difficult to find non-partisan comments so far, but here are some juicy ones:

- It’s ironic, or is it absurd or even obscene, that a group of well to do people, with top notch healthcare for themselves and their families, paid for by taxpayers, would be in a position to deny affordable health care to others.

- This year’s shutdown can be known as “Breaking Stupid.”

- Shut it down. I’ll save 25 minutes on my drive to work every day.